Black & White Luminaries: Insights into Adams and Garrett

Written By: SUSANNE LOMATCH

PAGE 3....

John Garrett is a distinctly different black & white photographer compared to Adams. His

career started as a fashion/beauty/advertising photographer in the ‘Swinging Sixties,’ and

he morphed into a newsprint photographer ("reportage" as he calls it) in the 70s. As such,

the films and techniques he uses are vastly dissimilar to those of Adams: grainy,

contrasty, fast films with compositions that focus on dark moody shadows and deep

contrasts, and in many cases, action. I first found Garrett’s compelling work from library

books, which I subsequently purchased [2,3].

John Garrett is a distinctly different black & white photographer compared to Adams. His

career started as a fashion/beauty/advertising photographer in the ‘Swinging Sixties,’ and

he morphed into a newsprint photographer ("reportage" as he calls it) in the 70s. As such,

the films and techniques he uses are vastly dissimilar to those of Adams: grainy,

contrasty, fast films with compositions that focus on dark moody shadows and deep

contrasts, and in many cases, action. I first found Garrett’s compelling work from library

books, which I subsequently purchased [2,3].

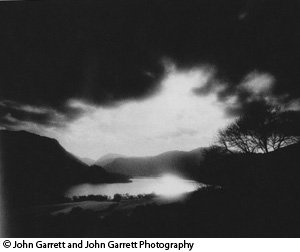

While I highly admire Garrett’s live action, portrait and fashion work, I found incredible

value in the transference of his photography techniques for those subjects to architecture

and landscape. My favorite is a shot he took of England’s Lake District, using Kodak

High-Speed Infrared film and a #25 red filter [refs. 2,3; pages 29, 8]. The deep grain and

red filter create a highly exaggerated image, offering a glimpse of an eerie-but-magical

lake through the jet-black outline of sky and foreground landscape. As Garrett points out,

simply shooting a fast, grainy film such as TMax 3200 with a red filter and a soft focus

can reproduce this imagery. I have found these effects also achievable with a lower rated

film and push processing, such as Ilford HP5+ shot and processed at 640 or 1250 ASA

(or even higher for more grain). In fact, I learned about these fast, grainy films and push

processing from Garrett. Overdevelopment sometimes makes a bold statement! In my

own application of Garrett’s techniques, I have emphasized the effect of making the

imagery look like a charcoal or pencil drawing, utilizing the additional technique of tone

reversal (solarization). Garrett didn’t use solarization, but I stumbled on the technique in

my processing for certain images that might never see the light of day without it.

In the digital era, these grainy, contrasty techniques can be reproduced by shooting at a

very high digital speed, say 3200 ASA, and using desaturation and color channel

blending techniques in Photoshop to render a final print. Grain can also be added using

Photoshop algorithms, though I must admit the intrinsic noise in photographic film is still

my favorite.

Garrett talks about his influences and his philosophies on B&W photography: "I grew up

with black-and-white images all around me…the newspapers, magazines, movies and

newsreels produced powerful black and white pictures that are indelibly printed on my

memory…I have no interest in photographic technique for its own sake…technique is

only the method to bring my visualization onto paper…Henri Carter-Bresson, Edward

Weston, and Richard Avedon were great masters, but you are bowled over not by

technical excellence, but by images [2]."

References:

[1] "Examples – The Making of 40 Photographs," Ansel Adams, Little, Brown and Co.,

1983. I didn’t read this book until very recently; it is a valuable and enlightening

resource. It includes details on photographs from Adams’ pedagogical series, Camera-

Negative-Print, interspersed with additional commentary and stories.

[2] "John Garrett’s Black-and-White Photography Master Class," John Garrett,

Amphoto Books, 2000.

[3] "The Art of Black and White Photography," John Garrett, Sterling Publishing Co.,

2003. (Original publication 1992 by Octopus Publishing Group.)